By Jennica Lynn Johnson

By Jennica Lynn Johnson

Does possession happen to people in real life? Is the Devil real? Tears streaming down my face, those were the kinds of questions weighing heavily on my mind after my first viewing of The Exorcist (1973). The fear of becoming Satan’s next vessel was instilled in me at nine years old.

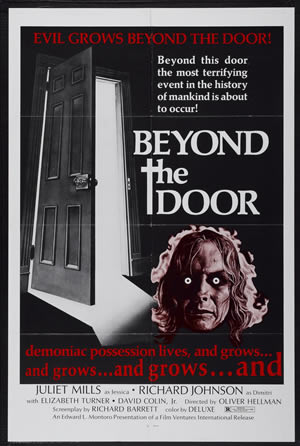

Since its 1973 release, The Exorcist inspired the production of many copycat films with Beyond the Door (1974) aka Che Sei? being the “most commercially successful,” according to Nikolas Schreck, author of The Satanic Screen: An Illustrated Guide to the Devil in Cinema. In fact, Beyond the Door star Juliet Mills confessed that the film was believed to resemble The Exorcist so closely that Warner Bros. had to be paid approximately $90 million. Although still loaded with as much shock value as The Exorcist, Beyond the Door reveals a sneakier, more seductive side to satanic culture and there aren’t any priests to save the day this time.

“Tonight I stand on the edge of eternity where she left me in the dark with self-despair. I’ve been turned away by Heaven. Now let the Devil hear my prayer.” Much unlike The Exorcist, in which musical scores such as Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells strictly serve the purpose of enhancing the heart-racing eeriness of the story, the music heard in Beyond the Door is almost like an omniscient character within the film.

The opening song, Bargain with the Devil, composed by Franco Micalizzi, is a funky little ditty which narrates the main plot of the story and sets the overall mood throughout the film. Bargain with the Devil tells the tale of a man, Dimitri (Richard Johnson), who has made a pact with the Devil to punish his former lover, Jessica (Juliet Mills), in exchange for immortality. What the song does not disclose is that Jessica was and still is married with children. Oh, and her punishment must be delivered in the form of satanic possession followed by Dimitri stealing her unborn child.

In addition to narrating the story, music is also personified to reflect the emotions of the main characters in the film. A case in point is when Jessica’s husband, Robert (Gabriele Lavia), is frantically running through the streets of San Francisco concerned for his now possessed wife.

As he begins to pick up his pace, a group of street performers begin following him and closing in on him, creating a nearly suffocating wall around him as they play jazzy tunes on their flutes and saxophones. The louder the music gets and the closer the musicians get to Robert, it is impossible not to feel his panic and desperation to get home to his wife and find a way to cease her suffering.

Another unique feature of Beyond the Door is definitely the blunt dialogue uttered so matter-of-factly by each character. It’s hard to miss Robert and Jessica joking about his secretary’s virginity or Robert complimenting Jessica’s “helluva great ass.” At first, one might be left wondering “What kind of couple talks to each other that way?” But perhaps the real question is “What couple doesn’t?” It is through their matching dark senses of humor that chemistry between Robert and Jessica can be found. There is a sense of comfort and playfulness to their conversations in which each knows the punchlines to the other’s wisecracks. Their relationship, unlike that of most fictional couples, appears genuine rather than a seeming attempt to create a Hallmark moment in every scene.

The truly stupefying element of the film’s dialogue, however, is the language of Robert and Jessica’s young children, Gaile (Barbara Fiorini) and Ken (David Colin Jr.). Although Ken’s use of profanity is easily explained away as mimicry of his older sister’s word choices; the film doesn’t waste any time when it comes to displaying Gaile’s adult view of the world, not to mention her view of her family, who appear to be the main targets of her obscene, condescending remarks.

No matter how many times I watch Beyond the Door, I am always so taken aback by Gaile’s sharp tongue that laughter inevitably follows my initial shock. The shocking part being, of course, that unlike The Exorcist’s foul-mouthed Regan, Gaile isn’t the one possessed in this film.

While the film’s music allows for continuity in the story, with the dialogue only adding to the bizarreness, there are occasional shots scattered about the film that encourage foreshadowing and hint that there is something terribly wrong with Jessica’s pregnancy. There is also a great amount of focus on fire as a symbol of damnation.

A clear-cut example of this is when Jessica is preparing for Ken’s birthday party. Jessica places the cake in the oven and the shot seems to be from the point of view of the cake as the flames arise from under the pan, and a worried expression takes over Jessica’s face. It is apparent that the cake is representative of Jessica’s unborn child.

I have been drawn to films about the occult and “the left hand path” since I was very young, and The Exorcist only strengthened my fascination. As a skeptic, the most intriguing aspect of such films is that they challenge my belief that what cannot be seen does not exist. Both The Exorcist and Beyond the Door—like many possession films—leaves room for an open discussion about the darker, more sinister side of religion. What is most terrifying about Beyond the Door specifically is that, from beginning to end, the film reminds its viewers that the Devil is an omnipresent force that cannot be seen or touched but could be hiding within any object or person. He could even be “that stranger sitting in the seat next to you.”

SOURCE: More Horror – Read entire story here.